The Silent Witness of Monza: A Son's Grief Amidst Royal Tragedy

Visiting Monza offers a chance to step beyond the well-trodden tourist paths and encounter a site that invites reflection on the complex interplay of personal loss and political upheaval.

For travelers venturing beyond the iconic Colosseum and the romantic canals of Venice, Italy holds quieter, yet equally poignant, historical sites. One such place is the Royal Villa of Monza, nestled in the verdant landscape near Milan.

While the villa itself whispers tales of royal life, a short distance away stands the Cappella Espiatoria – an expiatory chapel – a striking and somewhat unusual monument that speaks volumes about a nation's trauma and the silent grief of a son.

The chapel marks the exact spot where King Umberto I of Italy was assassinated on July 29, 1900. For visitors accustomed to a different relationship with monarchy, understanding this event requires a glimpse into Italy's late 19th and early 20th centuries—a period marked by social unrest and the rise of ideologies challenging the established order.

Umberto I was no stranger to danger, having survived two assassination attempts. However, the third attempt proved fatal on that fateful summer evening in Monza, as he left a sporting event. Gaetano Bresci, an anarchist who had returned from the United States with a burning desire for justice (or what he perceived as such), fired the shots that ended the king's life. Bresci's motivations were rooted in the brutal suppression of protests in Milan two years prior, where the army killed unarmed civilians under the king's authority. For Bresci and many others, Umberto I became a symbol of a system prioritizing the elite over the struggling masses.

News of the assassination reached Umberto's son, Vittorio Emanuele, the Prince of Naples, while he was enjoying a peaceful cruise in the Greek islands with his wife, whom he had recently married, Elena. Imagine the jarring contrast: one moment, the gentle sway of the yacht under the Mediterranean sun; the next, the shocking arrival of a vessel bearing the somber news of his father's violent death. The initial message spoke of illness, but the truth, stark and brutal, soon followed.

Vittorio Emanuele was suddenly King, described as reserved and intellectual, with a penchant for science and languages (6!) rather than grand public displays. Beyond the profound personal loss of his father, he inherited a nation grappling with the fallout of regicide and the underlying social tensions that fueled it. While historical accounts don't dwell extensively on Vittorio Emanuele's immediate emotional response, we can surmise the shock, disbelief, and the heavy weight of responsibility that descended upon him. He was no longer just a son; he was the head of state, tasked with navigating a turbulent political landscape.

Interestingly, Vittorio Emanuele's initial actions as king hinted at a desire for conciliation. He granted amnesty for press offenses and crimes against the freedom of labor, and reduced many of the sentences stemming from the very unrest that had motivated his father's assassin. Perhaps these acts were partly a silent acknowledgment of the grievances that had led to such a tragedy.

Today, the Cappella Espiatoria is a testament to this pivotal moment in Italian history. Its unique architecture, a blend of various styles, might strike visitors as unusual for a religious structure. This distinctiveness is a powerful reminder of the extraordinary and tragic event it commemorates.

As you stand before this chapel, consider not only the political ramifications of a king's assassination but also the personal tragedy that unfolded. Imagine the weight on a son's shoulders, suddenly thrust into leadership amidst national mourning and unrest. While the history books focus on the grand narratives of power and revolution, the Cappella Espiatoria silently echoes the more intimate story of a son's grief. A royal family irrevocably changed, forcing a nation to confront its internal divisions.

The Cappella Espiatoria, in its solemn beauty, poignantly reminds us that even within the grand stage of history, the human heart, with its capacity for both love and sorrow, remains central.

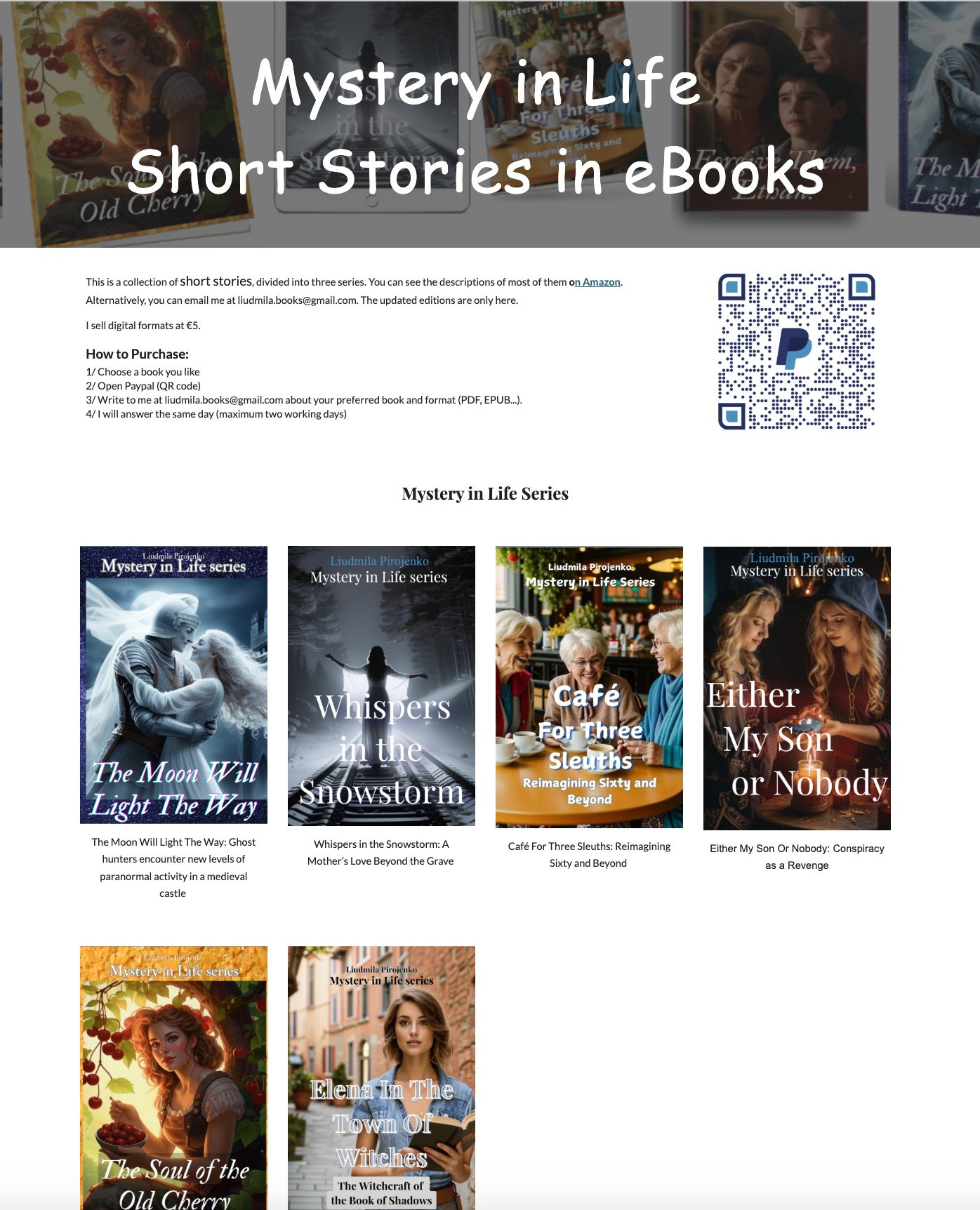

ARE YOU INTERESTED IN OTHER STORIES?

You can find my books here: https://bit.ly/MysteryinLife

Seriously....I am not a huge history buff...but I love food (especially pasta and pizza)....and wine. Hence my lifelong interest in the country....but I can not justify a cross Atlantic trip for food...some I am working on coming up with reasons that my husband...and maybe even my mom would like to visit. Is Tuscany all its cracked up to be? If I had 7 days...where should I spend 2 of them?

I have always wanted to visit Italy....will keep this post in mind!